About this deal

Shore's photographic work and professional success was undoubtedly informed and assisted by his friendships with many significant postwar artists. His relationships at the Factory, MoMA, and the Metropolitan Museum had developed into a network that included Ed Ruscha, Dennis Oppenheim, Christo and Jean-Claude, Garry Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander. Shore is recognised as being among the most influential post-war American photographers, and was included in the landmark exhibition New Topographics: Photography of a Man-Altered Landscape at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House, Rochester, New York in 1975 (alongside photographers including Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams and Bernd and Hilla Becher). His work is closely associated with conceptual practices as a result of his time at Andy Warhol’s Factory in the 1960s, and he is credited, along with William Eggleston (born 1939), with helping to establish colour photography as a valid medium. Shore returned from that initial road trip with nearly 100 rolls of film, which he developed as any ordinary person would: He sent them to a Kodak factory in New Jersey. He then showed the snapshots in New York’s LIGHT Gallery in 1972. The art world was not enthused, but Shore continued the project anyway. He kept photographing places around the country (and a few in England) through 1973. This same year, he switched to the large-format camera, first a 4x5 and later an 8x10. Content inseparable from attention to form. It occurs to me that there’s no such thing as a definitive Steven Shore photograph, except that it’s by default like nothing else. I recognize it, but not as an instance of “style.” It’s more like entry to a zone of immediate experience. I feel a little lost, as I do in my real life. You don’t pin down; you unpin up, if that makes any sense. Shore was born in New York City in 1947, the sole son of Jewish parents who ran a handbag company. At the age of six, he began to develop his family’s photos with a dark-room kit his uncle had given him as a present. He received his first camera a couple years later, and when he was ten he received a copy of Walker Evans’ American Photographs.

VH: The images in the book really capture the full spectrum of life, from the whimsical and humorous to the introspective to the downright messy – do you find yourself gravitating to one of these more than the others? Shore's photographs often appear as unstudied snapshots before revealing themselves, on closer examination, to be carefully calculated and balanced. His images show a deep consideration of framing, with lines and colors chosen to emphasize the formal qualities of the places or objects within the frame, heightening the viewer's focus. SS: Not necessarily, and when I said I didn’t have a problem editing down, I meant I didn’t feel an obligation to include everything. There’s a lot of work, and the current edition has grown out of looking at some of the pictures that didn’t make it into the previous edition. There were a lot of pictures in the original show in ‘72 that were not included in the previous Phaidon edition of American Surfaces. When The Museum of Modern Art gave me my retrospective in 2017, the curator of the show, Quentin Bajac, wanted to recreate the American Surfaces show. I continued for about half a year photographing for the project after the show went up so Quentin could avail himself of the entire body of work. We decided to expand the original Phaidon book to include those. From here, it’s going to feel like I’m skipping forward for a moment. The American Surfaces series was shot between 1972 and 1973, but it wasn’t published as a proper book until 1999 – nearly three decades later! Before this, it existed merely as a gallery exhibition. Shore was just 24 years old at the time he took these images, yet served another full lifetime in this respect when the book was eventually published at age 51. At the time that this series became a book, his life – and his career for that matter – were very different.Today, Shore is the director of photography at Bard College, where he started as a professor in 1982. He wears tortoiseshell glasses and a wardrobe of corduroy, wool, and tweed. His hair is gray and slightly wild. He appears so adapted to the professorial role that it’s a surprise to learn that he has almost no formal schooling of his own. By geographically and chronologically charting the photographer’s original footsteps, the book becomes a supra-documentary, re-centering its focus with each new form of the work, making the larger undertaking its own best subject. Shore has referred to both this and the expanded re-issue of another of his books as the equivalent of “director’s cuts”, but that single metaphor shortchanges the larger implications at hand. To begin with, this reincarnation of American Surfaces as a kind of meta-work might be read as positioning the book questionably within an educational or service function, rather than as a sui generis aesthetic form. Considering at least part of its origin within a conceptual milieu, this becomes doubly problematic. What such a book might benefit from as a historically corrective omnibus version becomes its liability as a less potent incarnation of original art. This is not a fault of this edition specifically however, so much as the larger trend towards photography book re-issues, as one might consider the case to be with the latest edition of Walker Evans’ Many Are Called, among others. This photograph is striking for its intimacy; the subjects appear aware of Shore's camera, but unperturbed by it. The famous figures in the images are captured in an unguarded, human and apparently ordinary moment. Shore's talent for recognizing the value of the everyday and capturing it is clear in this image, which would later serve as a document of an important cultural moment. The lighting, soft yet bright, creates a sense of ethereality, as does the grain of the image, which is particularly apparent in the textured hair and clothes of the figures at the foreground, at once heightening their inaccessibility and their apparent reality in a manner that accords with the mythical status Warhol's Factory and its denizens would attain. In 1972, you chose to present “American Surfaces” unmatted, unframed, and taped to the wall—very Warholian. The approach was met with a scathing reception, but today that sort of casualness seems intrinsic to how we consume images. Do you think people have changed their way of seeing? That was Shore speaking to Gil Blank in 2007. And this is him speaking to his publisher, Phaidon, in a promotional interview five years later:

The fly-fishing comparison still holds, and his images, though no longer surprising, still evince intelligence, concentration, delicacy and attention. It’s the earliest work that intrigues the most, though, insofar as it shows the tentative emergence of a modern American master. Shore took this photograph, along with others during his first year working on Uncommon Places, with a 4 x 5 Crown Graphic camera, wishing for greater accuracy with framing and a higher quality image than had been possible with his Rollei, despite the challenges this posed in taking the photographs he desired. This image required Shore to stand on a chair and raise the camera, attached to a tripod, above him on an angle. The apparent simplicity of the image, which erases Shore's authorial presence and the difficulty with which the camera was balanced, is belied by the shapes, lines and framing, all of which reveal the photograph as deeply considered. The diagonal lines of the placemats at the top and right hand side direct the audience's eye into the image, the framing of the pancakes by the plate and placemat marks this area of the image as particularly significant and the interplay of small and large circular items serves to hold the audience's attention and stimulate sustained consideration.

Customer reviews

This image, from Shore's best-known series, Uncommon Places, shows a table set for breakfast at what appears to be a diner. The breakfast setting, on a table lined with a lamination imitating wood, is positioned on a diagonal from the camera. It consists of a plate of pancakes, encircled by Hopi petroglyphs, positioned between cutlery atop a placemat showing scenes of Native Americans and white colonizers. Further from the camera, occupying a central position at the top of the frame, is a smaller plate upon which sits a bowl holding half a cantaloupe. To the right are a salt shaker and a pepper shaker, a glass of water with ice and a glass of milk. In the lower left corner, the tan acrylic of the seat below is visible. I went to the view camera really for a simple reason that I wanted to continue with American Surfaces, but I wanted a larger negative to make bigger prints, because film at the time wasn’t very sharp,” he said. Look at the first Uncommon Places photos and the continuity with American Surfaces is obvious: For instance, he shoots his hotel television and bed. Soon, however, the images move away from interior spaces toward large images of neglected architecture, parking lots, and street intersections, . I do think about why people are all of a sudden looking at my work,” he told me 10 years ago, “and it occurs to me that it may have needed a distance in time for people to see what I was actually looking at. People need time. It’s much easier to look at the past than to look at the present.” Stephan Schmidt-Wulffen was born in 1951 in Witten/ Germany. He works as an art theoretician and director of the art academy Akademie der bildenden KA1/4nste in Vienna/Austria.

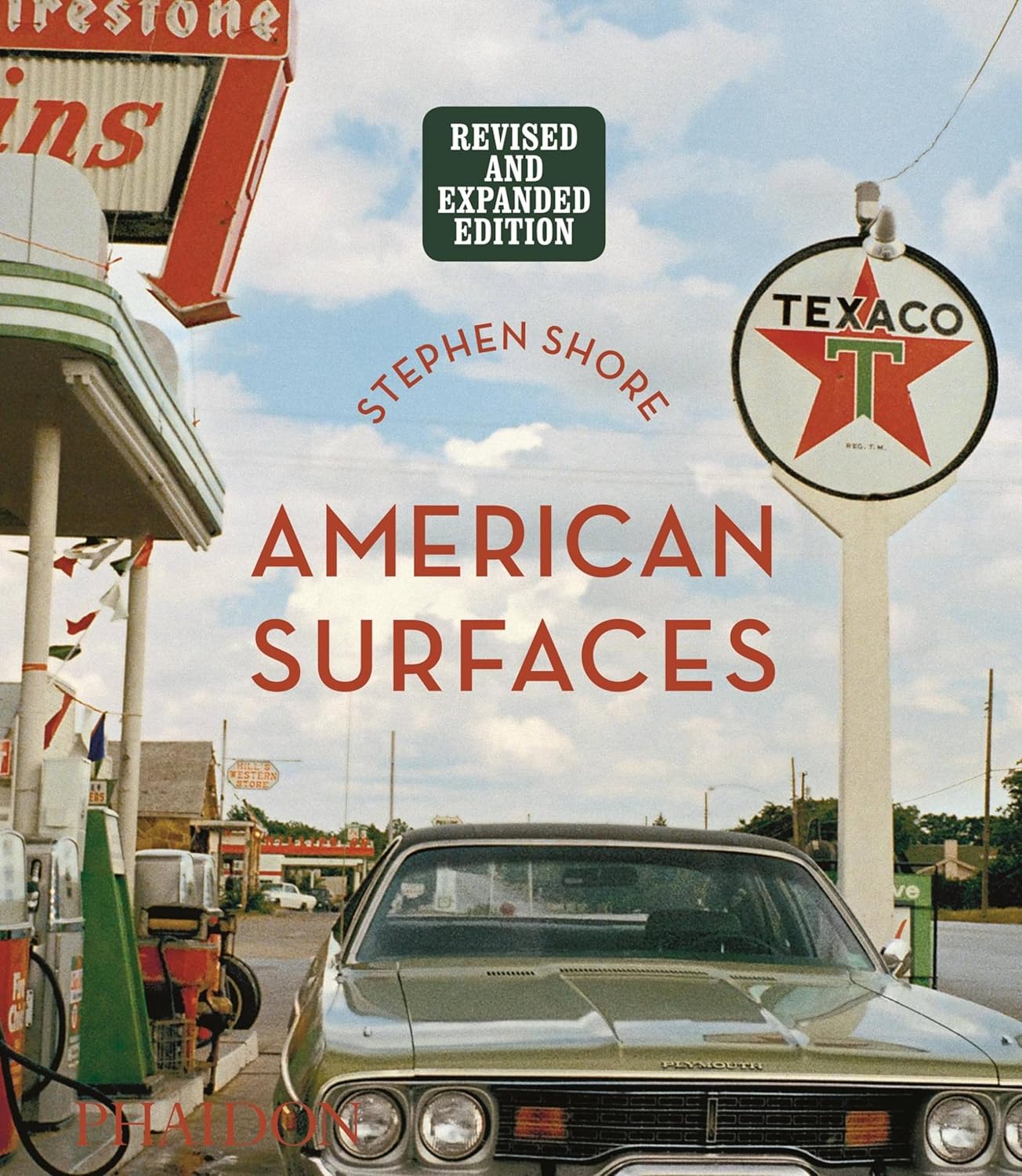

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you. This photograph of an intersection in Oklahoma is among the image sequence known as American Surfaces, taken on Shore's first drive across the United States. At the centre of the image is the point where two roads intersect, marked by a set of traffic lights and a vertical sign marking the Texaco station visible behind two cars on the right side of the image. The image has been taken late in the day and the lights are bright against the faded blue and orange sky, the dark green of the nature strips and the grey of the road and the foreground parking lot in which crumpled newspapers lie discarded. American Surfaces is intended to be seen as a sequence, in which the minor details of life on the road, including food on tables, beds and televisions in motels and gas stations such as this, build to communicate a sense of the North American interior as an anonymous monotony. In June 1972 the 24-year-old photographer and native New Yorker Stephen Shoreset off on a road trip, driving south, through Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas, into the deep South and Southwest. Reflected in the title of the work, the details recorded in American Surfaces are superficial, yet together they build a bold and insightful portrait of the social and geographical landscape specific to North America at that time. Prior to making American Surfaces, Shore’s work had focused almost singularly on New York, where he grew up. This project marked a formative point in his career when the concept of the road trip became – as it remains – integral to his practice: immediately after finishing this project he began his seminal series Uncommon Places (published 1982). Working in a photographic tradition established by American photographers such as Robert Frank (born 1924) and Walker Evans (1903–1975), in American Surfaces Shore established a new method of recording vernacular scenes of life in North America. The artist has stated that he set out to record ‘everything and everyone’ he came across (Stephen Shore, artist talk, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, 23 February 2012, http://www.americansuburbx.com/2012/01/asx-tv-stephen-shore-sf-moma-artist-talk-2012.html, accessed 21 November 2014). His approach – loosely diaristic and serial in nature – together with his non-hierarchical framing of the image and grid-like method of presentation, indicated links with minimalist and conceptual practices of the 1960s and 1970s.VH: Absolutely! Thank you so much for speaking with me and with Phillips. We’re really excited about the new edition of 'American Surfaces.' It’s an unexpected statement coming from the man who made American Surfaces. But then American Surfaces was not the random result of some photographic compulsion: Shore conceived of and executed it as a disciplined artistic undertaking. “I think there may have been a slight difference,” Shore said about the symmetry between these photos and social-media photography. “When people are posting, I actually find it a little peculiar. Why would they think that I would be curious what they had for breakfast? But this was more a way of using my own experience as—it was about me, but it was also about exploring the culture through this mechanism [the snapshot].” American Surfaces was first published as a book of seventy-two images in 1999. In 2005, consistent with his practice of revisiting and reworking earlier series through the medium of the photobook, Shore published the series in its entirety for the first time, and applied a cohesive structure to the works, grouping them by year and the state in which they were taken (see Shore 2005). These digital prints owned by Tate were made in the same year in an edition of ten.

All great American photographs have one thing in common: power lines. This is not, strictly speaking, true. But it often feels true, especially when you look at street photography. Electricity tends to follow our roadways, just like documentary photographers. So power lines inevitably appear in their pictures. And the way an individual photographer confronts them can illuminate his style of seeing. You can observe Walker Evans’s mastery with the camera, for instance, in his treatment of power lines. He admitted them into photographs not, like most of us, by unhappy necessity, but with formal artistic intention.No one was better at it than he was—except for maybe Stephen Shore. I believe Uncommon Places to be about photography showing the beauty of everyday life, while American Surfaces displays the beauty of photography itself by reflecting itself within banal scenes of normality. There is place for both frames of mind, and I actually believe an understanding of the trade-offs between these two reference points is vital for any photographer today.VH: You were born in New York City but your journey took you through small-town America. Were you looking to photograph communities that felt familiar to you or those that felt different from where and how you grew up? As a teenager, Stephen Shore was interested in film alongside still photography, and in his final year of high school one of his short films, entitled Elevator, was shown at Jonas Mekas' Film-Makers' Cinematheque. There, Shore was introduced to Andy Warhol and took this as an opportunity to ask if he could take photographs at Warhol's studio, the Factory, on 42nd Street. Warhol's answer was vague and Shore was surprised to receive a call a month later, inviting him to photograph filming at a restaurant called L'Aventura. Shore took up this offer and, soon afterward, began to spend a substantial amount of time at the Factory, photographing Warhol and the many others who spent time there. He had, by this point, become disengaged with his high school classes and dropped out of Columbia Grammar in his senior year, allowing him to spend more time at the Factory. For 22 months beginning in March 1972, Shore traveled across the continental United States with a simple Rollei 35 – a camera so diminutive in stature that it earned the title of smallest 35mm camera in production at the time [ more on the Rollei 35 can be seen here in our review]. It was this tiny camera which allowed him to blend in, to never give the air of a serious photographer, and which granted him accessibility to people and places without question or query. It was the normality, the civilian nature of a compact 35mm loaded with color film which let him make important work right under the noses of people looking for Leica-clad members of Magnum.

Related:

Great Deal

Great Deal